by Muskan Dhandhi

I’m currently pursuing my PhD in English Literature and Translation Studies at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Mandi, India. My PhD explores Intersemiotic and Experiential Translation within Haryanvi Women Folklore including Haryanvi rituals and material culture by documenting, translating, and analysing these oral, visual, and performative traditions. Haryana, a state in Northern India has a rich array of various oral narratives, rituals, traditions, etc. However, neither this nor the fact that there exists a Haryanvi culture is acknowledged by many researchers. During the initial years of my PhD, I realised that this under-representation of Haryani Folkore within academic research is due to a lack of documentation. Hence, it becomes imperative to document the rituals celebrated across the state and the associated material culture in the form of visual art on the walls, clothing, and jewellery before it all disappears because of modernization of the society that results in an exodus from the villages in pursuit of better opportunities.

This summer I travelled to the UK with a Charles Wallace Short Term Research grant in order to access Haryanvi material culture (inc. Haryanvi women’s clothing and jewellery) in the UK.* This included examining textiles from 1800s Punjab at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, as well as audio-visual archives including images and videos pertaining to undivided Punjab (as Haryana was a part of Punjab till 1966).** I also met with various researchers working in the area of Intersemiotic and Experiential Translation.

My primary objectives for my proposed visit were:

- Understanding transfer of meanings between non-literary sign systems in Haryanvi material culture including clothing and jewellery.

How can transfer of meaning (translation) between multimodal, multilingual, and multicultural spaces (such as translating images, translating music, etc.) take place coexisting with a language, cultural and modal barrier? - Formulating a relevant research methodology in analysing the relationship between Intersemiotic and Experiential Translation and Material Culture in conversation with community knowledge and Haryanvi Folklore.

Since these material objects are culturally embedded visual and performative texts, how can they be translated within a non-literary sign system? What kind of research methodology is required for the above and what impact does it create on the pre-existing translational theories of practice?

*I will never forget the day when I received the email for receiving Charles Wallace India Trust Grant for visiting the UK. I was over the moon. I was thrilled and honestly didn’t expect that. It is an honour to have received this prestigious grant and I would like to thank Charles Wallace India Trust for their unconditional support.

**Earlier this year, I had also received a Shastri Indo Canadian MITACS Globalink Research Award for spending a semester in Canada where I am currently documenting the Haryanvi rituals Ahoi Asthami and Dev Uthan Ekadashi as performed by Haryanvi Indo-Canadians. I am so happy my research is receiving such supportive recognition from key awarding bodies.

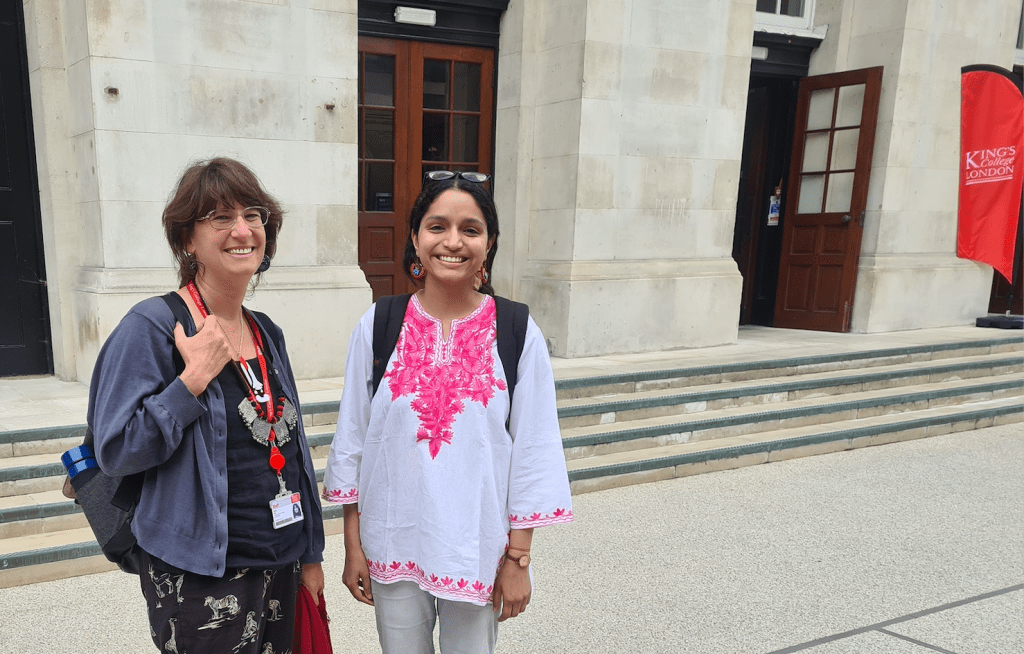

During my visit, I met Dr. Ricarda Vidal, Dr. Madeleine Campbell, and Prof. Piotr Blumczynski with an objective to understand their research on these processes. During my meeting with Dr. Vidal at King’s College London, she provided insightful suggestions and comments on the project, discussed theoretical paradigms and current research developments in the field and suggested some readings. She also talked about her research findings with regards to experiential translation and ongoing research projects. I later travelled to Edinburgh and met Dr. Madeleine Campbell at University of Edinburgh. We discussed our ongoing research work and her forthcoming publications on Experiential Translation. We discussed the need for a translation movement such as the Experiential Translation Network, including the role of language and media, and viewing intersemiotic translation and experiential translation as a way of meaning making in cross cultural communication. I also met Prof. Piotr Blumczynski at Queen’s University Belfast. As much as the previous meetings were beneficial for my research, this meeting was highly fruitful as he discussed his recent book Experiencing Translationality: Material and Metaphorical Journeys (May 2023). His book pertained to translating relics and artifacts through Translation and thus established the process of translating materiality. Apart from discussing challenges he faced while translating such material objects, he also shared significant observations about my project and provided a road map to encounter hardships on the way.

Through my visit and with generous and insightful suggestions for my research from these researchers, I formulated relevant cultural-specific research methodology in analysing the relationship between Translation and Haryanvi Material Culture. As these material objects are culturally embedded visual and performative texts, my research answers how culture can be translated across a digital age. Haryanvi culture and heritage must be preserved for forthcoming generations. Such cultural preservation can take place when subjected to necessary documentation and translation for a multicultural, multilingual, and multimodal society, which again will promote a nuanced understanding of Haryanvi culture.

If not documented, not only will such objects and traditions die, but communities will also no longer have access to their socio-cultural identity. Preservation and subsequent translation of such folkloric traditions also empower the community members, performers, and audience, and hence strengthens the sociocultural fabric of a nation. Thus, it is of utmost importance that Folkloric traditions must be protected, conserved, and translated to maintain social harmony.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank my PhD supervisor Dr Suman Sigroha for always being there for me as a mentor and a friend and motivating me to work hard. These awards have encouraged me to work hard and have motivated me immensely to represent the Haryanvi culture and community worldwide. I hope to work even harder and better and will give my best in the years to come.

Muskan Dhandhi is a PhD Research Scholar and Teaching Assistant at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi, India.

[like] Terry Bradford reacted to your message: ________________________________

Very interesting research project. You might like to consider framing it as inter-epistemic translation and linking it to our EPISTRAN project (www.epistran.org). Piotr can advise you about that – he’s one of our consultants.

Brightest and most hardworking PhD scholar I know 🙂 keep it up!