by Harriet Carter and Ricarda Vidal

In 2021 and 2022 we conducted a series of workshops exploring asemic hand-writing. We wrote about these on this blog and in a book chapter1 which will be published in April 2024. Writing the blog helped us clarify our ideas which we then took further in the book chapter, but we’re far from having exhausted the subject…

In fact, writing our way through the complexities of meaning-making in mark-making only amplified the enticing call of uncertainty which is so much part of the asemic experience. And so we have teamed up again to return to the asemic, though this time with a specific focus on asemic nature writing, a subject which has been hovering on the periphery of our vision for a while but which we have not yet had the time to explore more deeply.

While we conducted our research with the poets, painters and text-makers of Ledbury and Montpellier during 2021 and 2022, we were also invited to lead a workshop with fine art students in the Forest of Dean [Thank you to the amazing Level 4 undergraduate Fine Art students from the University of Gloucestershire!]. For this we introduced students to the works of Cui Fei and Zhu Yingchun, amongst others, before we asked them to go out into the woods and create their own text or encounter with nature from what they found there.

We are still not sure what happened in the forest and in the creation of these texts. Nor do we know what they tell us of the forest or of ourselves.

But we feel they are a good starting point for us to explore what asemic nature writing could be or do and how it might help us shed light on the ways in which the very human nature of attempting to make sense of the world relates to encountering the more-than-human elements within nature. In our next blog post we will discuss the forest workshop in more detail.

Nature has asemic qualities in the ways that we could consider it to have a language that is indecipherable to us. Rainwater and sunlight communicate with organisms, trees communicate with mycelium networks, birds communicate with each other to provide invitations for eligible mates, or warnings to foes. To suggest these forces of nature operate within the “elsewhere”2 of our understanding – outside of our language – highlights that we can only encounter and explore nature through an anthropocentric lens. Here we must steer clear of the age-old human exceptionalism, the notion that humans are somehow outside of nature.

As Cronin suggests, rather than looking at “what makes [humans] distinctive from other beings” we need to shift our focus to “[e]xploring what is held in common”; in fact Cronin talks of this as nothing less than “a strategy for survival”.3

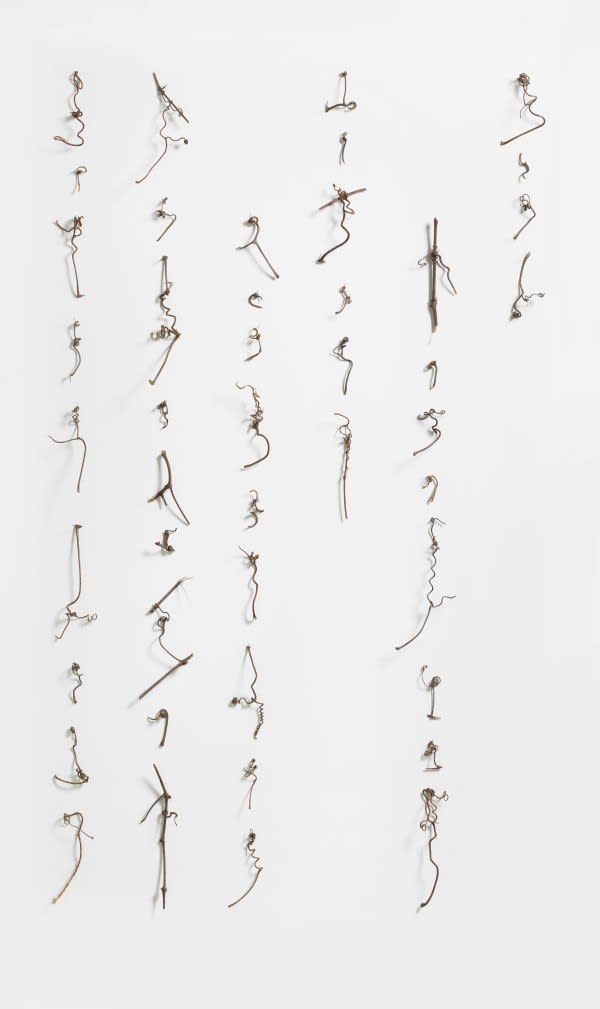

Cui Fei’s reflections on her asemic creations are a beautiful example for such a potential exploration of commonalities. The artist’s practice emerges from understanding the concept of nature as one that emphasizes the interconnectedness of all beings and an opportunity to explore the relationships between nature and human beings.4 The creation of her Manuscript of Nature series speaks about this. By “composing manuscripts” using materials found in nature (e.g., tendrils, leaves, thorns), Cui Fei explores the symbolizing of “nature’s voiceless messages that wait to be discovered and heard”.5 The resulting sculptural works are asemic texts that undermine conventional language because they look like writing (Chinese characters) but aren’t. Cui Fei’s use of the word “composing” is particularly intriguing. It connotes notions of collecting, piecing together found material in a new context, and inventing connections. In the case of the Manuscripts of Nature series, composition is with material distant to the human conventional sphere of operating.

Ontologically speaking, this asemic text talks only about the connection between sculpture and the tendrils used to create it. We cannot read the text that is authored by the artist or by the voiceless tendrils – at least not in a conventional sense. Graham Harman states that humans are closed off from the “inner sanctum” of an object both conscious and unconscious.6 Does this mean that both unconscious objects and conscious animals in nature have hidden inner spaces to each other and to humans? But also, does it make sense to speak of “unconscious objects” in the first place…. Is it even possible to differentiate between conscious and unconscious, between animate and inanimate, as we have done for centuries in Western thinking? We’re not so sure. And we don’t know yet how far down the metaphorical rabbit hole we will pursue this question.

Much like with our experience of the asemic, when encountering other agents in nature (flora, fauna, creatures, light, wind, aroma), we bring our own language systems to make sense of something that is distanced to our comprehension. Just like asemic writing ultimately is about writing itself, the things that inhabit nature speak about nothing more than their ‘nature’ as nature. We wonder whether to enter into the world of asemic nature writing, we have to become more-than-human, or rather, as Cronin and Badiou would prefer, “acknowledge our animality”.7

But for now we are wondering why asemic texts like Cui Fei’s speak to us. Or, in fact, why the pattern of a wood worm on tree bark makes us think of coded messages. If we look for it, asemic writing is all around us. Nature, one could think, is full of traces and marks waiting to be read… and it is true, these marks are there to be read, though not necessarily by us. In an attempt to bridge the artificial divide between humans and the more-than-human and explore the commonalities between us, we want to explore further what happens if we try to read the asemic texts of nature. And, as with our previous forray into the asemic, reading will also entail tracing, drawing, and writing, because, as we’ve argued previously, learning to write facilitates the learning of reading.8

Nature is ephemeral, it lives and breathes in a spatio-temporal realm where things come and go. As things that also come and go, we are keen to explore how encountering nature might be seen as a sort of asemic event. We see this asemic event as intrinsic to the human’s presence; it is borne through embodied encounter with nature. Yve Lomax talks about an “event” as being made up of five facets: evanescent, supplement, chance, the incalculable, and the origination of truth.9 We can map the very moment of encountering nature with these points.

Ricarda: Lomax’s book Sounding the Event needs some introduction here. It is one of those books you need to sit with, to sit with and to think with. At best not anywhere near a screen, but somewhere outside surrounded by wide vistas and the noises of nature, or, in fact, in a social setting, in a pub with the rumble of conversations and the beat of music.

Harriet: I came across Lomax during my PhD when I was trying to make sense of what encountering birdsong is like and how we can get our heads around drawing birds’ intangible song, and movement through the air. I saw stepping into the landscape to bear witness to these feathery creatures as situating myself in an event in space and time in Lomax’s sense: In Sounding the Event Lomax has a surreal ‘conversation’ with philosopher Alain Badiou. She questions encounters with nature and time, using Badiou’s description that an event is made up of the five parts mentioned above, all of which together constitute a situation in the world, that occurs in the here-and-now. I have found that these five parts happen simultaneously and that I can tease them out in the experience of birdsong.

In her PhD Harriet found that listening to, and transcribing birdsong was bound in the very moment of perceiving and that this was an embodied encounter.10 This moment of perceiving birdsong is an event in the wider situation of humans existing in nature – an event of stepping into focus if you will, or as Cronin eloquently puts it, to sit still and pay attention.11

If we stand in the forest alone, and hear birdsong, the birdsong moving unseen through air is evanescent (Lomax describes this as “something that vanishes from ‘being’ as soon as it appears”12). This interaction of sound passing into our ears is a supplement (something extra to what “is”13) – in this case, that we have stepped into the landscape bringing our ears into a natural habitat that exists outside of our being. The supplementing of a person into this scene, creates moments where chance can occur14, the effect of which is incalculable to the wider situation in which the encounter takes place. In other words, the encounter speaks about itself, and does not identify how birdsong is encountered for other people or how it might be encountered next time. This experience of birdsong is a truth, i.e., the encounter happened, or to paraphrase Lomax; without an event, there is no truth.15

We are one with nature, albeit human, we share a form of animal-ness. Indeed, Cronin says that “nature is what holds the voices of the universe” (from the Big Bang, appearance of life and multicellular organisms, and humans)16. Nature tells a story “of events that are contingent and unpredictable” where humans are part of this but they “do not define it”.17

In her PhD, Harriet found that experiencing birdsong as an event had a metaphysicality to it all – it is intangible and unpredictable. Further, she argued that making marks during this moment of perception is a drawn event. We also explored this with the students in the forest (and with the participants of our asemic writing workshops) when we asked them to listen and to let sound guide their mark-making.

To explore the (im)possibilities of tapping into communication between beasts and vegetation, we note the anthropocentricity that we embody when encountering nature. Much like our previous findings about the asemic, we have to acknowledge that the context of our ‘beingness’ brings certain ideologies and material implications to what we have learnt to perceive of as alien territories.

And so we set out into the wild on the next leg of our asemic journey into uncertainty, ears, eyes and noses wide open to nature in and around us.

- Vidal, R. and H. Carter. 2024. ‘The Productive Embrace of Uncertainty: Asemic Writing, Drawing, Translation.’ in M. Campbell and R. Vidal, eds. The Experience of Translation: Materiality and Play in Experiential Translation. London and New York: Routledge, pp.79-96. ↩︎

- See birdsong in Carter, H. 2022. Beyond Transposition? Exploring metaphysicality in birdsong and Olivier Messiaen’s Catalogue d’oiseaux through painting practice. PhD thesis. Birmingham City University. Available at: https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.876169 [Accessed: 6 January 2024]. ↩︎

- Cronin, M. 2017. Eco-Translation: Translation and Ecology in the Age of the Antrhopocene. Abingdon: Routledge, p.69 ↩︎

- See Cui Fei’s artist statement about the Manuscript of Nature series: http://cuifei.net/about/cui_fei_statement_Manus.htm ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Harman, G. 2005. Guerrilla Metaphysics: Phenomenology and the Carpentry of Things. United States of America: Open Court Publishing Company, pp.250-259 ↩︎

- Cronin, 2017, p.68 ↩︎

- Vidal and Carter, 2024 ↩︎

- Lomax, Y. 2004. Sounding the Event: Escapades in Dialogue and Matters of Art, Nature and Time. London: I.B. Tauris, pp.163-167 ↩︎

- Carter, 2022: p.119 ↩︎

- Cronin, 2017, p.20 ↩︎

- Lomax, 2004, P.163 ↩︎

- ibid. p.165 ↩︎

- ibid. p.163 ↩︎

- ibid. p.171 ↩︎

- Cronin, 2017, p.29 ↩︎

- ibid. p. 29 ↩︎